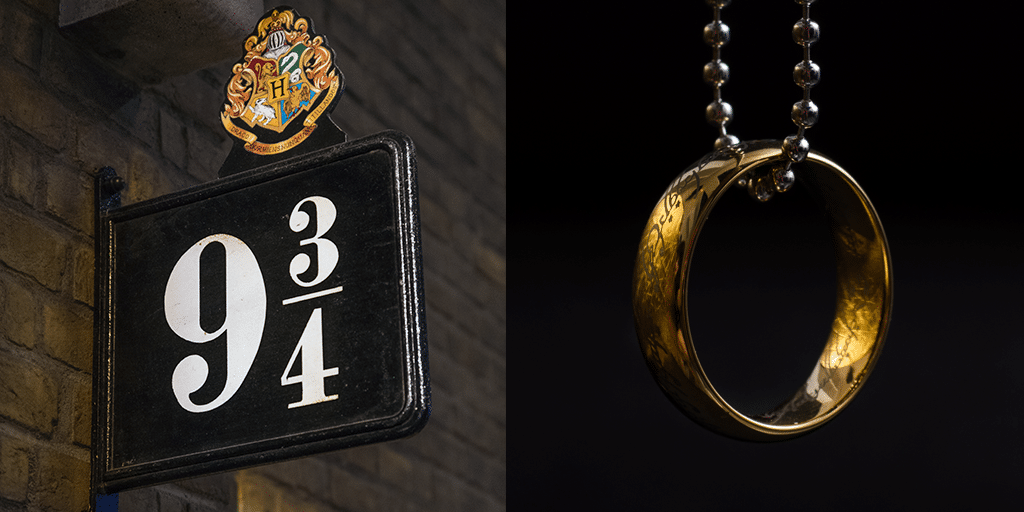

The Difference Between “Harry Potter” and “Lord of the Rings”

| By: Dr. Tom Snyder; ©2003 |

| Should we just see both Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings as fantasy and just leave it at that, or are there deeper issues we need to address? Dr. Snyder points out some areas of difference. |

The Differences Between Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings

Recently, a Christian website equated The Lord of the Rings, both the book and the movie versions, with Harry Potter. The website was full of misinformation, however, that will confuse visitors.

Although The Lord of the Rings is not about witchcraft, it does have a character in it, named Gandalf, who is called a wizard and a sorcerer by other characters. Also, in the movie version of the first book, The Fellowship of the Ring, he wields a wooden staff which has special powers.

Having a wizard in a story is a moral problem, because the Bible condemns sorcery. Of course, Christians can treat the Bible verses against sorcery in their grammatical-historical context, where such things are condemned in real life, as real human beings do them, not as fictional characters doing them in a story that is meant to be a fantasy. However, if we take that approach, then that might make Christians think that Harry Potter is perfectly okay. This is exactly what some Christians have actually done.

In The Lord of the Rings fantasy, however, Tolkien treats Gandalf as a special created being. Unlike Harry Potter and his friends, Gandalf is not a mortal human being, and neither are the magical immortal elves in the story, who have magical powers, use magical incantations and such. Thus, Gandalf and the elves have magical power given to them by a creator, although in the Tolkien background stories, there is no reference to the Bible. Furthermore, the staff that Gandalf uses seems similar to the staff that God gives Moses to use in the Bible.

Also, in The Lord of the Rings, the power of the evil magical ring is not something to be sought, but to be shunned and destroyed. The human characters in the first movie, Boromir and Aragorn, are encouraged to avoid the power of the ring. Boromir fails, and he dies. Even Gandalf and the magical elves shun the power of the evil ring. This is much, much different than the magical power in the Harry Potter series, where the use of magic and witchcraft is accepted and encouraged by the human characters.

Most importantly of all, perhaps, The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter have a different ontology, a different view of the nature of reality. In The Lord of the Rings, reality is real, and actions have real consequences. In Harry Potter, however, the characters can manipulate reality through witchcraft, and are encouraged to do so. As a result of Harry Potter’s viewpoint, Harry Potter and his friends get away with telling lies and disobeying rules. In fact, at the end of the second Harry Potter movie, the school officials cancel exams for all the students in the witchcraft school!

I never met a metaphor that walked on all fours. Works of art should be treated in a figurative, symbolic manner, not just a literal way. Christians have the same problem that the Marxist and feminist film scholars I encountered at Northwestern University had. They are tempted to use their theology/worldview to attack every single thing in a work of art that smacks of evil. The problem is, however, although every artist and filmmaker has a theology and a worldview, every artist and filmmaker is not as polemical about it as the Marxist, feminist or Christian would like them to be. In fact, many popular artists just use the cultural and sociological milieu in which they live, whether that be a capitalist one or a pagan one, as the canvas on which they paint. Thus, an artist might have a capitalist or a pagan hero, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the artist is trying to push some kind of capitalist or pagan worldview on the viewers, especially in the polemical way that a Marxist or Christian artist might wish to do.

Thus, J.K. Rowling is probably not a member of some coven, though she could be (she probably reflects, however, the politically-correct moral relativism of her pagan environment), and Tolkien is not just some Christian theologian trying to re-create a world where one-to-one Christian symbols occur, as C.S. Lewis often did in his books of The Chronicles of Narnia. Thus, Lord of the Rings is full of neo-Norse mythology and even perhaps fantasy references to occult mythology in his description of wizards. (It is also true that his use of the English term for tobacco, “weed,” has been picked up by the pot smokers, but that doesn’t make Tolkien an advocate for the legalization of marijuana.)

Therefore, there is a certain sense in which Christians should take these kinds of fantasy works as just that, fantasy, and give the artist a little benefit of the doubt. This is something that many Marxists and feminists do not do, because they have no golden rule and no relationship with a merciful God on which to base their lives. The Marxists and feminists looked foolish when they condemned a movie like John Ford’s The Searchers for still being racist, even though, at the time, the movie presented a very anti-racist message. Christians who misrepresent The Lord of the Rings and use an emotion-based, inaccurate hermeneutic will also look foolish in the end if they persist. Our goal should always be to inform other Christians about media-wisdom, using a biblical approach that is intellectually sound.