What is the Trinity?

What Is the Trinity?

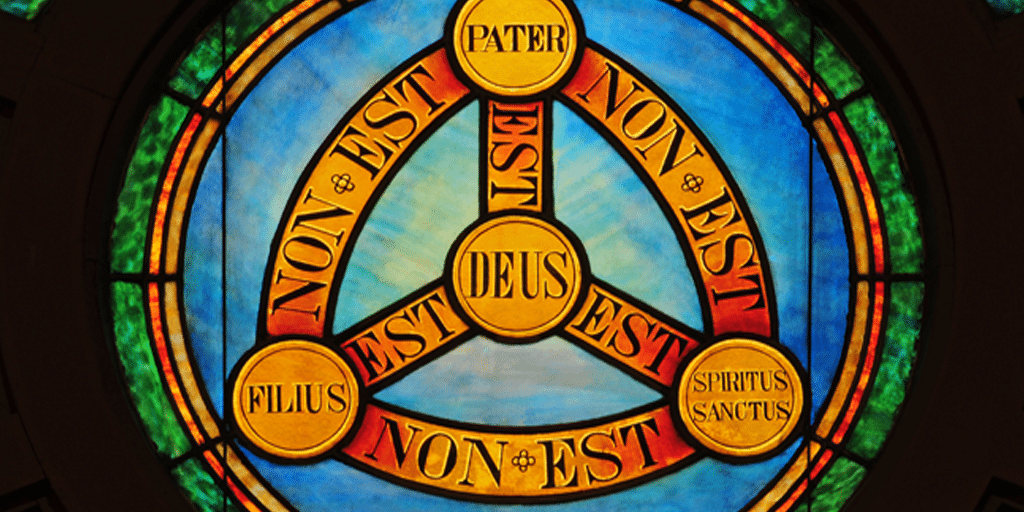

The basic belief in Christianity is that one true God has revealed that He is three Persons, or centers of consciousness, within one Godhead. Because the concept cannot be fully comprehended does not mean the doctrine is irrational or cannot be accurately defined. What is the Trinity? A good definition of the Trinity is provided by noted church historian Philip Schaff:

- God is one in three persons or hypostases [distinct persons of the same nature], each person expressing the whole fullness of the Godhead, with all his attributes. The term persona is taken neither in the old sense of a mere personation or form of manifestation (prosopon, face, mask), nor in the modern sense of an independent, separate being or individual, but in a sense which lies between these two conceptions, and thus avoids Sabellianism on the one hand, and Tritheism on the other. [Sabellianism taught that God was one person only who existed in three different forms or manifestations; tritheism refers to a belief in three separate gods.] The divine persons are in one another, and form a perpetual intercommunication and motion within the divine essence. Each person has all the divine attributes which are inherent in the divine essence, but each has also a characteristic individuality or property, which is peculiar to the person, and can not be communicated; the Father is unbegotten, the Son begotten, the Holy Ghost is proceeding. In this Trinity there is no priority or posteriority of time, no superiority or inferiority of rank, but the three persons are co-eternal and coequal.[1]

The biblical doctrine of the Trinity is vital to understand because it concerns who God is, which is essential for having a proper realization of the nature of God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. To understand the Trinity is to understand God as He has revealed Himself to be. To misunderstand the Trinity is to fail to understand who God is.

This is important because if we are to worship God “in spirit and truth” (John 4:24), as Jesus commanded, we must know and worship the one true God as He really is. To fail to do this is to fail to know and worship God, and this cannot bring Him glory. Thus, those who reject the Trinity by definition deny the nature of God. Without a biblical theological formulation about God, heretical views arise. This in turn can lead to rejection of the one true God and the worship of a false God. And if the Bible is clear on anything, it is clear that faith in a false God cannot save people from their sins. Jesus Himself emphasized the importance of having an accurate knowledge of God when He said, “This is eternal life: that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

In his Christian Theology, Christian theologian Millard J. Erickson offers six points that must be included in a proper understanding of the doctrine of the Trinity (the following is the authors’ paraphrase of Erickson’s points):

- There is only one God

- Each Person in the Godhead is equally deity.

- The threeness and oneness of God constitute a paradox or an antinomy – merely an apparent contradiction, not a genuine one. This is because God’s threeness and oneness do not exist in the same respect; that is, they are not simultaneously affirming and denying the same thing at the same time and in the same manner. God’s oneness refers to the divine essence; His threeness to the plurality of persons.

- The Trinity is eternal – there have always been three Persons, each of whom is eternally divine. One or more of the Persons did not come into being at a point in time or at some point in time became divine. There has never been any change in the essential divine nature of the triune God. God is, and God will be what God has always been forever.

- The function of one member in the Trinity may for a time be subordinate to one or both of the other members, although this does not mean that that member is in any way inferior in essence to the others. Each Person of the Trinity has had, for a period of time, a particular function unique to Himself. In other words, the particular function that is sometimes unique to a given Person in the Trinity is only a temporary role exercised for a given purpose. It does not represent a change in His status or essence. When the second Person of the Trinity incarnated and became Jesus Christ, He did not become less than the Father in essence, although He did become subordinate to the Father functionally. In like manner, the Holy Spirit is now subordinated to the ministry of the Son (John 14-16) and to the will of the Father, but He is not less than they are. Certain examples may illustrate this. A wife may have a subordinate role to a husband, but she is also his equal. Equals in some business enterprise may elect one of their number to serve as head or a chairperson for a period, without any change in rank. During World War II, the highest ranking member of an aircraft, the pilot, would nevertheless carefully subordinate his decisions to the bombardier, a lower ranking officer.

- Finally, the Trinity is incomprehensible. Even when we are in heaven and fully redeemed, we will still not totally comprehend God, because it is impossible that a finite creature could ever comprehend an infinite being. Thus, “Those aspects of God which we never fully comprehend should be regarded as mysteries that go beyond our reason rather than as paradoxes which conflict with reason.”[2]

Prior knowledge of the Trinity, especially in its theological formulation, is not necessary for a person to be saved. But once saved, it is vital for Christians to know the true nature of the God who has so graciously pardoned them. This explains why the Church has always recognized the importance of a proper understanding of God and maintained that those who reject the scriptural view of God, as long as they do so, cannot be saved. Consider Dr. Schaff’s comments about the Athanasian Creed:

- [It] begins and ends with the solemn declaration that the catholic [universal] faith in the Trinity and the Incarnation is the indispensable condition of salvation, and that those who reject it will be lost forever. This anathema [divine curse], in its natural historical sense, is not merely a solemn warning against the great danger of heresy, nor, on the other hand, does it demand, as a condition of salvation, a full knowledge, and assent to, the logical statement of the doctrines set forth (this would condemn the great mass even of Christian believers); but it does mean to exclude from heaven all who reject the divine truth therein taught. It requires everyone who would be saved to believe in the only true and living God, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, one in essence, three in persons, and in one Jesus Christ, very God and very man in one person.[3]

As Vladimir Lossky once put it boldly, “Between the Trinity and Hell there lies no other choice.”[4] Only personal bias or ignorance can explain cultic attempts to deny the biblical Trinity. It is significant that even some Unitarians who reject the Trinity still confess it is a biblical teaching based on “its obvious sense, its natural meaning” as found in Scripture. These words of George E. Ellis, a nineteenth-century Unitarian leader, illustrate the biases of anti-trinitarian groups and liberals who refuse to accept the Trinity on personal, not biblical, grounds. Ellis confesses, “Only that kind of ingenious, special, discriminative, and in candor I must add, forced treatment, which it receives from us liberals can make the book teach anything but Orthodoxy.”[5] No less an authority than the great Princeton theologian B. B. Warfield pointed out that the doctrine of the Trinity “is rather everywhere presupposed” in Scripture.[6] This is, for example, clearly demonstrated in Edward Bickersteth’s fine work, The Trinity.

Go Deeper

Notes

- ↑ Philip Schaff, ed., rev. by David S. Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom: With a History and Critical Notes—Vol. 1: The History of the Creeds (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1983). The Greek term was transliterated by the authors.

- ↑ Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1986, one vol. edition), pp. 337 338.

- ↑ Schaff, ed., Creed, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (1957), p. 66.

- ↑ In E. Calvin Beisner, God in Three Persons (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1984), p. 25.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 26.