Logical Criteria for Determining Error and Truth – Part 1

One of the earliest professions that I trained for was the law. And I came to appreciate the standards that are, theoretically at least, maintained in law courts when it comes to the handling of evidence. And this is going to be the kind of exercise of logical criteria for determining error and truth, which is very pertinent to the kind of confusion or even readiness to misinterpret on the part of the scholarly fraternity that has endeavored to discredit the Scripture from the standpoint of accuracy, inerrancy, authority. Let’s how to the logical criteria for how to determine error and truth.

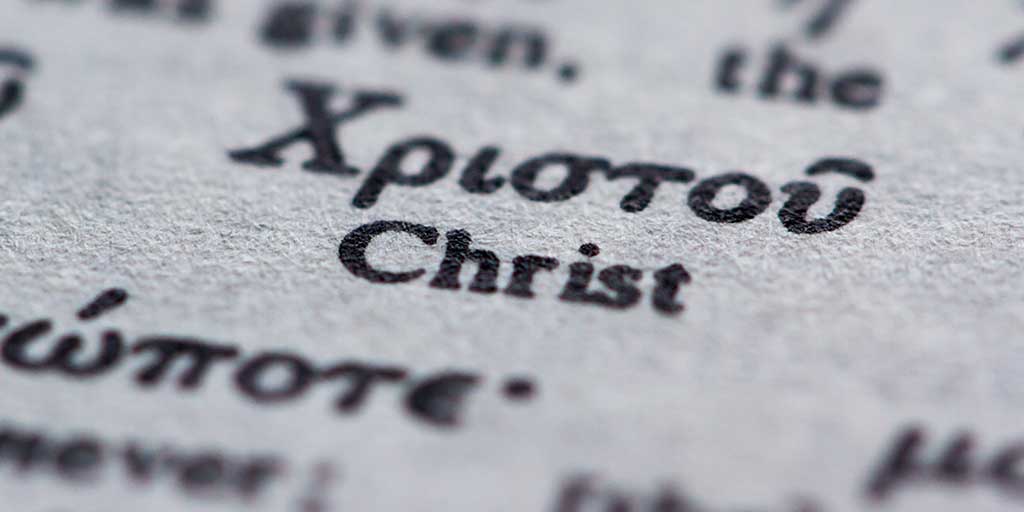

And what we need to understand is that the great majority of the alleged errors rest upon a background of ignorance concerning the languages in which the Bible was composed. Well over 50%, I find, of the questions that were raised during the years when I was writing along this line for Decision magazine had to do with an ignorance of either Greek or Hebrew or Aramaic. And so I want to preface my remarks that the only way you can deal with these matters adequately is to master those languages.

Now, there are certain recommended procedures that I would like to suggest at the very beginning when you come up against what looks like a discrepancy in the Scripture.

First of all, you need to be fully persuaded in your mind that there is an adequate explanation, even though you don’t know yet what it is. The aerodynamic engineer may not understand how it is that a bumblebee could fly, because its wings seem to be too small to carry all of that weight. Yet he sees him fly, and so he has to trust that there must be an explanation for his flying performance.

Even so, we may have complete confidence that the Divine Author of Scripture preserved the human author of each book from error or mistake as he wrote down the original manuscript of the sacred text, what is technically known as the “autograph,” which is a little different from signing your name on somebody’s Bible flyleaf.

Secondly, avoid the fallacy of shifting from one a priori to another—to its opposite—every time a problem arises. For the Bible either is the inerrant word of God, or it is the imperfect record of fallible men. And once we have come to the insight and agree with Jesus that the Scripture is completely trustworthy and authoritative, then it’s hardly pertinent for us to shift over to the other assumption: that the Bible does contain errors and therefore must be subjected to intelligent human judgment to weed out the mistakes from the truths.

You see, unlike all other books known to man, the Scriptures come to us from God, and in them we confront the ever-living, ever-present God. When we are unable to understand God’s ways or comprehend His words, we must simply bow before Him in humility and wait for Him to clear up the difficulty or to deliver us from our trial if we are in a situation that is critical.

Thirdly, carefully study the context and framework of the verse in which the problem arises until you get some clear idea of what the passage is intended to mean within its own setting. It may be necessary to study the entire book in which the passage occurs, carefully noting how the key term is used in other passages. Compare scripture with scripture, especially all those passages in other parts of the Bible that deal with the same subject or doctrine.

Fourthly, remember that no interpretation of scripture is valid that is not based on careful exegesis. Now exegesis is the science of eliciting the full meaning of the author from the words that he used, within an understanding of the grammar and the lexicography that is involved. Now you have to use and be able to employ good dictionaries in Hebrew and Greek, and you have to study parallel passages.

To give you a familiar type of example, suppose you are a foreigner and you have come to America, and you’re trying to learn the English language. You look up in the dictionary and you find the word “strike” has a variety of meanings, but perhaps it would still be confusing to you if were to read in the newspaper, “The prospectors make a strike yesterday up in the mountains.” And then in another column you read, “The union went on strike this morning.” And then perhaps in another page, “The batter made his third strike and was called out by the umpire.” And then when it comes to the performance of a band, it says “Strike up with the Star-Spangled Banner,” or “The fisherman got a good strike in the middle of the lake.” Now, presumably each of these completely different uses of the same word go back to some apparent meaning and would have a definite etymology. But a complete confusion may result from misunderstanding how the speaker meant the word to be used.

I remember there was a dear lady from Hong Kong who said, “I thought I knew something about the English language when I came to this country, and I saw a dog. Yes, a dog: that’s a little animal that has four legs and a waggly tail. But then I heard that some people were saying that “their dogs were tired,” and they didn’t even have a dog with them. And then there was quite a bit of bad weather that came along, and I was told that it was “raining cats and dogs,” but I didn’t see any. And then there was this lady that went around with very fancy clothing and I was told that she was “putting on the dog,” but I didn’t see any dog.”

Well, you see, what you have to do is learn to understand what people mean by the language which they use, rather than what you would infer from your knowledge of the terminology.

Continued in Part 2

Ed. Note: This article is excepted and slightly modified from our program, “Answers to Assumed Errors in the Old Testament.”