Were the Days of Creation 24 Hours Long?

In our last article, we examined how Moses presents a different order of events within Genesis 2 than he did in Genesis 1 – particularly the order of God creating Adam and then the animals. This diverse ordering is not due to misinformation or multiple authors. Rather, their shared thematic emphases evidence a high degree of intentionality and harmony. This shows us that Moses has chosen to arrange his presentation of God’s historical creation, or at least portions of it, thematically rather than chronologically.

Other Non-Chronological Arrangements in Scripture

Since this can be a novel concept for many of us, and possibly even troubling at first to some, I want to devote an article showing how this approach is not abnormal for Moses or the biblical authors in general. Although we as modern readers typically assume that historical accounts need to give a precise chronology of events in order to be accurate, this was not the case in Moses’s day or antiquity in general. They gave far more attention and care to arranging their material thematically than we ever think of doing. Because of this, breaking with chronology was allowed. Helping an audience readily grasp the significance of an event and be able to retell it later was of chief importance.

Although there are many instances of non-chronological arrangement, space limits us here, so let’s just consider three from Moses and then one from the Gospels where the material is arranged out of order to stress a thematic point.

Days of Creation: Genesis 10-11

One example of Moses choosing a thematic rather than chronological arrangement can be found in Genesis 10 and 11. In Genesis 10, Moses presents us with the Table of Nations – outlining the decedents and nations that came from Noah’s three sons. However, in Genesis 11, Moses goes back in time to tell us how the scrambling of these nations all came about. Although Moses doesn’t specifically tell us in chapter 11 that he has gone back in time, the text makes this clear. How?

In Genesis 10, Moses mentions how Noah’s decedents were scattered throughout the earth with each of the nations speaking their own language. Genesis 11, however, opens with the whole earth speaking the same language. It then goes on to explain how the scrambling of languages and scattering nations came about. You can see these details in the verses below.

“the nations were separated into their lands, every one according to his language, according to their families, into their nations” (Genesis 10:5).

“These are the sons of Ham, according to their families, according to their languages, by their lands, by their nations” (Genesis 10:20).

“These are the sons of Shem, according to their families, according to their languages, by their lands, according to their nations” (Genesis 10:31).

“Now the whole earth used the same language and the same words…. the Lord confused the language of the whole earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of the whole earth” (Genesis 11:1, 9)

Now if Moses wanted to follow a chronological arrangement, he would have presented the Table of Nations after the Tower of Babel. So why does he reverse these? It appears he is more concerned with emphasizing an overall theme: he wants us to see Abraham as God’s gracious response to His judgment upon of the nations’ sin. We find in Genesis 12:3 that it will be through God’s blessing upon Abraham and his seed that “all the families of the earth will be blessed” (NASB).

(If you are looking for a fun study, I recommend reading Acts 2 in light of this account pertaining to the scattering of the nations.)

Exodus 18

Another instance of Moses arranging his material non-chronologically can be found in Exodus 18. In this account, Moses’s father-in-law, Jethro, goes out to visit Moses when he hears how God brought the Israelites out of Egypt. In verse 5 we read that Jethro and his family went out to “where [Moses] was camped, at the mountain of God [referring to Mt. Sinai].”

This detail is noteworthy because the account of the Israelites arriving at Mt. Sinai does not occur until the next chapter (Exodus19). It appears that Moses has intentionally placed the story of Jethro here (breaking with the books overall chronology), because He wants us to read it in relation to the previous account: the story of the Amalekites going out to attack the Israelites. By juxtaposing these two groups who go out to meet the Israelites, the kindness of Jethro the Midianite is highlighted against the hostility of the related Amalekites.

Furthermore, both of these opposing encounters devote significant space to emphasizing a common theme: Moses’ need for help given the weight of his task. When the battle against the Amalekites lasted until sunset, Moses needed help holding his arms up because “his hands were heavy” (Exodus 17:12); then, when Jethro observes Moses settling disputes from sunrise to sunset, he advises Moses to teach the people God’s ways and to appoint godly leaders “because the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone” (Exodus 18:18). As one can see, Moses intentionally places this material out of chronological order to highlight these themes.

Numbers 1-6 and 7-9

Again, we find Moses organizing sections within the book of Numbers out of chronological order. Let’s focus on Numbers 1-6 and 7-9. Fortunately, Moses establishes the timeframe for each of these sections which helps us follow his otherwise confusing timeline of events. Although they all take place within the same year, the events of Numbers 1-6 take place during the second month while the events of Numbers 7-9 take place during the first month. Thus, Numbers 7-9 actually takes place about a month before Numbers 1-6 even though Moses tells us about them later. Below is a brief look at how we come to know this.

Numbers 1 opens with the timeframe, “on the first day of the second month of the second year after the Israelites came out of Egypt” (Numbers 1:1).

But when we get to Chapter 7, Moses specifies that he is going back in time to “When Moses finished setting up the tabernacle” (Numbers 7:1). We can determine when this was from Exodus 40:17, “So the tabernacle was set up on the first day of the first month in the second year” (Exodus 40:17). Thus, in chapter 7, Moses jumps back to the first month of that year. This first month remains the setting in Numbers 9 as well when Moses states, “in the first month of the second year after they came out of Egypt” (Numbers 9:1). [1]

The lack of chronological arrangement continues further in chapter 9.

The first section (vv. 1-14) primarily focuses on when the Israelites “observed the Passover on the fourteenth day of the first month at twilight” (Numbers 9:5). Verses 6-15 record a question that arose on that Passover day followed by God’s responding instruction. In short, it almost entirely focuses on the fourteenth day.

However, when we come to the second section (vv. 15-23), we find Moses taking us back in time once more. It opens, “On the day that the tabernacle was set up [the first day of the first month of the second year].” This section goes on to recapitulate the account in Exodus 40:34 with added detail.

As you can see from these few examples, Moses has no problem breaking from a chronological telling of events. After observing so many instances of this, ancient Jewish interpreters even developed the saying, “There is no chronological order in the Torah.”[2] While this is certainly an overstatement, it illustrates the commonality of this tendency.

Given that Moses often presents events outside of their chronological order, we should, therefore, not assume or require his accounts to be chronological. In most cases, Moses’ thematic arrangement coincides with the actual order of events. However, we need to cautiously follow his textual clues because it is not uncommon for him to depart with chronology in order to stress the theological significance of an event.

The Order of Events in the Gospel Accounts of Jesus’ Temptation

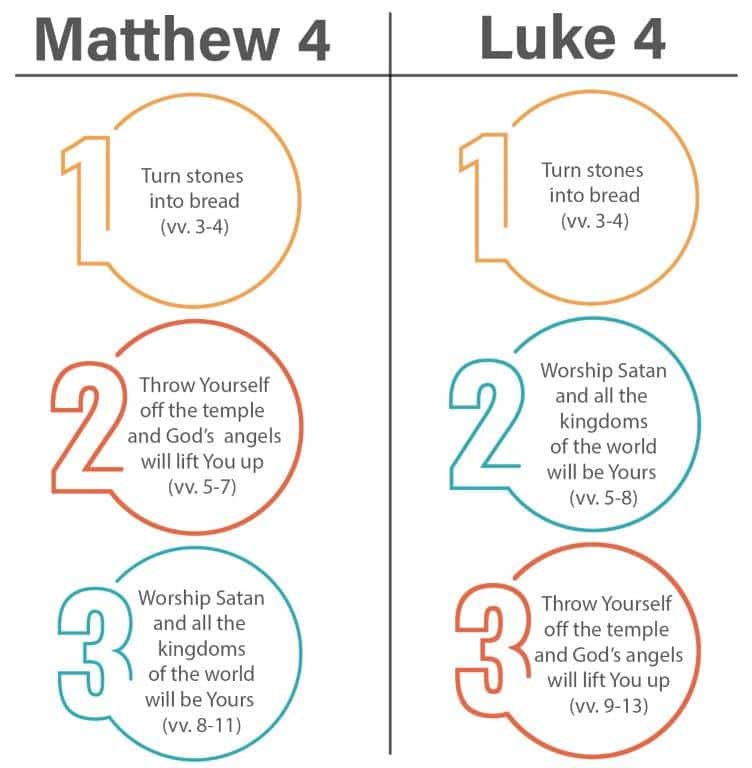

Clear examples of thematic rather than chronological arrangement can also be found in the New Testament. Take for example Matthew and Luke’s accounts of Jesus’ temptation during His forty days in the desert. While Matthew and Luke record the same three temptations, they do so in differing orders. Thus, at least one has chosen to arrange the material thematically rather than chronologically (most consider Luke’s account to break with the chronological order in which the events actually occurred).

Here is how each Gospel records these events:

Although their ordering of events is different, both authors use their arrangement toward the same end: to show how Jesus, through His obedience to the Father, will ultimately overcome not only a particular temptation but Satan himself. Both Gospels conclude with Jesus rightfully receiving from the Father what Satan last used to tempt Jesus. In both accounts, the geographical location of Jesus’ final temptation matches a significant location within that Gospel and is also the place where that book concludes.

Matthew

In Matthew, Jesus’ last temptation happens upon a mountain, a key geographical setting in his Gospel. As one may recall, it is upon a mountain that Jesus begins His ministry (with the Sermon on the Mount) and it is upon a mountain that Jesus gives His final charge to the disciples (the Great Commission).

It is in this closing account (the giving of the Great Commission) that Matthew brings the themes related to Jesus’ last temptation to their climatic end. Although Satan tried to tempt Jesus with “all the kingdoms of the world” (Matthew 4:8), Matthew shows us in his closing account how Jesus eventually received from the Father what Satan falsely sought to offer: “All authority in heaven and on earth” (Matthew 28:18). In fact, Jesus received not only all authority on earth, but also all authority in heaven – something beyond what Satan offered.

Furthermore, in contrast to Satan’s request for worship (“All these things I will give You, if You fall down and worship me”; Matthew 4:9 NASB), Matthew’s Gospel ends with Jesus being worshiped by His disciples (“And when they saw [Jesus], they worshiped Him”; Matthew 28:17 NASB). The term here for “worship” or “bow down” plays a prominent role in Matthew’s Gospel. He uses the term 13x – more than twice as often as Mark (2x) and Luke (3x) combined.

Seeing the geographical importance Matthew gives to mountains, his unique mention of the Great Commission, and his focus on worship, it is not surprising that Jesus’ last temptation in Matthew is the one that culminates in all these themes.

Luke

In contrast to Matthew, the third temptation in Luke’s Gospel recalls how the devil brought Jesus “into Jerusalem and had Him stand on the pinnacle of the temple” (Luke 4:9 NASB).

The devil then urged Jesus to jump saying,

“If You are the Son of God, throw Yourself down from here; for it is written: ‘He will give His angels orders concerning You, to protect You,’ and, ‘On their hands they will lift You up, so that You do not strike Your foot against a stone’” (Luke 4:9-11 NASB).

Interestingly, this final temptation touches on at least two themes that are unique to Luke: Jesus’ resolute journey to Jerusalem (with Luke’s Gospel concluding at the temple), and Jesus’ ascension (something only described in Luke’s Gospel). Let’s take these one by one, starting with Jerusalem.

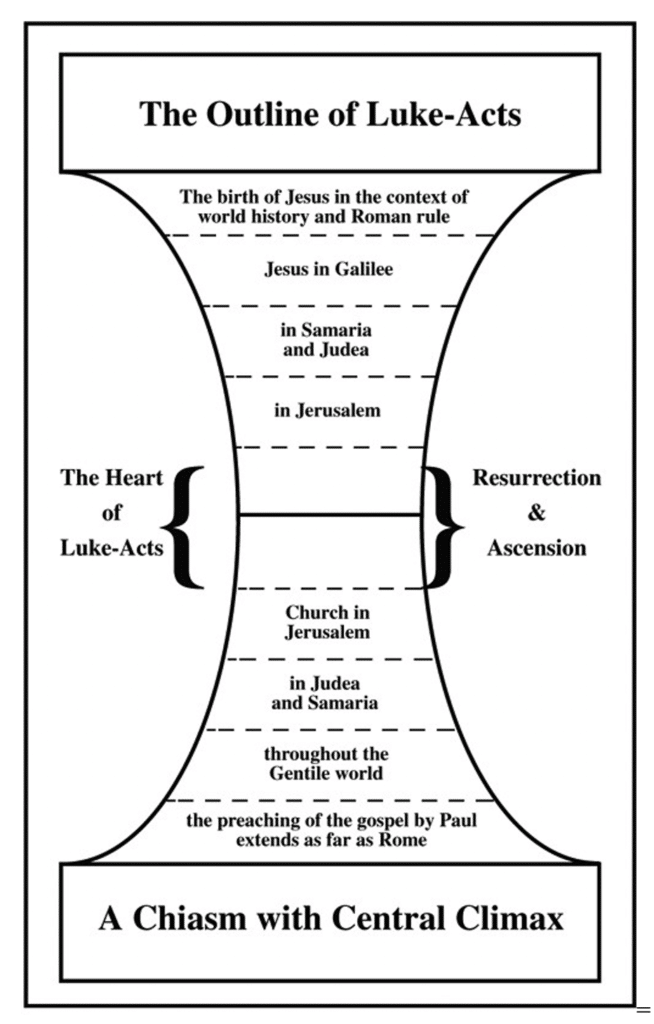

The Gospel of Luke and the book of Acts are tied together around two journeys: Jesus’ journey into Jerusalem to accomplish salvation and the disciple’s journey out from Jerusalem to proclaim this salvation to the ends of the earth. Many scholars note how Luke purposely arranged these two books around this geographical framework. Below is a chart by New Testament scholar, Craig Blomberg, which gives a visual summary of this.[3]

It is noteworthy that Luke devotes over a third of his Gospel to the travel narrative in which “Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51 NIV). To fit this travel sequence, Luke purposely omits and rearranges some of Mark’s material. Whenever Matthew or Mark mention an event’s location that doesn’t fit Luke’s geographically arranged account, he purposely makes no mention of it. For example, although both Matthew and Luke specify Caesarea Philippi as the location where Peter declared Jesus to be the Messiah (Matthew 16:15; Mark 8:27), Luke intentionally removes this detail from his account (Luke 9:18-27). By doing so, he maintains the appearance of Jesus remaining in Galilee. This is just one of the examples which show the intentionality that Luke gives to geography and the centrality he assigns to Jerusalem. Thus, it makes sense that Luke would culminate with Jesus’ temptation in Jerusalem on top of the temple. It also makes sense that this is the final location mentioned in His Gospel, “Then [the disciples] worshiped [Jesus] and returned to Jerusalem with great joy. And they stayed continually at the temple, praising God” (Luke 24:52-53; NIV).

Along with His unique emphasis on Jerusalem, Luke is the only Gospel to record Jesus’ ascension into heaven: “While [Jesus] was blessing them, He parted from them and was carried up into heaven” (Luke 24:51 NASB).[4] What a great way to end! Here the verse cited by the devil comes to awaited climax: God preserves Jesus’ life and has Him carried up. Moreover, look at how Psalm 91 (which was cited the devil about angels lifting Jesus up) continues on in the next verse: “you will trample the great lion and the serpent” (Psalm 91:13 NIV). Rather than striking his foot against a stone, it will trample upon the serpent. Once again, Luke shows us that the promise of this verse came about not through giving way into temptation but through Jesus’ obedience to the Father.

Seeing how each author focuses on these concluding themes helps us understand why they chose to arrange their temptation account in the manner they did. Although Matthew and Luke present a different order of events, they do so to draw out unique aspects of the same theme: Jesus’ triumph – not only over temptation, but ultimately the devil himself.

Together, these examples from Moses and the Gospels give us few snapshots into the prominence biblical authors placed on thematic arrangement – with them sometimes even departing from the chronological sequence of the actual events in order to stress a particular theme. These non-chronological arrangements were not due to misinformation or myth. They were intentionally employed to highlight the account’s theological significance. As we looked at in our last article, this appears to be the case with Genesis 1-2 as well.

Go Deeper with Your Faith

- Ultimate Prophecy Package

- The Biblical Case for the Rapture of all Christians – 2021 Package

- Join the Inner Circle of Friends

[1] Here is a link if you would like to explore this further: https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-message-of-the-non-chronological-opening-of-numbers

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/There_is_no_chronological_order_in_the_Torah

[3] Craig Blomberg, Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey, Second Edition (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2009), p. 162.

[4] Jesus ascension is also mentioned in the longer ending in Mark (Mark 16:9-20; see v. 19). However, since the longer ending is not included in any of the earliest manuscripts and is not considered to be a part of the original Gospel, I have excluded it from the consideration above.